Confessions of a Photobook Addict

Dear Reader,

On this day, October 14th, 2019, the 166th anniversary of the publication of the world’s first photobook (Photographs of British algae: Cyanotype impressions, by Anna Atkins), I make the following confession to you:

I am a photobook addict.

Only in this realm and in this realm only have I—and do I still—exhibit all of the characteristic behaviors of a classic gambler/addict: manic compulsiveness (if I don’t buy this now I will end up buying it on the secondary market for three times as much), magical thinking (if the books from Japan arrive when I alone am at home, I was meant to have this—these—tomes regardless of cost or the cost of judgment), irrational rationalizations (I have never seen this book for sale and it is the last one I need to complete my collection of X Photographer’s work), and marriage-threatening levels of personal spending (um…not disclosing that even to you, dear reader).

What was my initial gateway drug? Probably actual books with more words than images, and getting a reader’s high with first editions and full collections of specific author’s works. With regards to photography, I believe I was first lulled into acquisitive complacency with the Phaidon 55 series and/or the Photo Poche/Photofile series.

The first actual artist-made book I bought happened when I was in graduate school (and likely with student loan money that I will be forever paying off), and was an early publication of Masao Yamamoto’s, the Nakazora scroll, with Nazraeli Press. I had fallen in love with his first body of work, A Box of Ku, which I had seen at the Jackson Fine Art Gallery near where I had grown up and was living prior to studying photography in earnest. I wasn’t quite prepared for what I saw there, or the reaction I would have to his work: the niggling sense of familiarity, of shared sympathies or concerns. The Greeks had a word for it: anagnorisis, meaning literally a recognition of someone, not only of their person but of what they stand for and represent. I had also never encountered exhibition hanging styles like the kind he was favoring at the time: no frames, no hierarchy of viewing, viewing his work in person felt more like an experience of a murmuration of photographs than the typical sterile gallery visit.

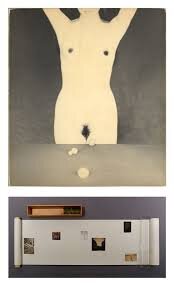

Masao Yamamoto installation view, Jackson Fine Art Gallery, 2003.

Masao Yamamoto exhibition installation view, Craig Krull Gallery, Santa Monica, 2004.

Yamamoto is what I like to think of as a photographer’s photographer. His images do things without a specific end goal in mind, and they work on the subconscious in ways that artists like to linger on. His photographs are not fussy, pushy or over-determined. There is something perversely liberating in our over-professionalized field in just enjoying imagery that is expansive, agenda-less and, as gauche as it is to admit it, beautiful. Much of the power and delight for me in Yamamoto’s work is his seeming opposition to many of the prevailing conventions on what makes a successful photographic image, project or career.

His images have no narrative, no agenda, no point to prove. He takes open-ended Buddhist concepts as a point of departure and titles his shows with these words that have multiple and overlapping meanings: A Box of Ku (i.e. “emptiness); Nakazora (“the space between sky and earth,” “An internal hollowness”) and Kawa (“Flow”).

The staging and installation of his work is highly personal, organic and non-orthodox in gallery culture. Hundreds of small images climb and descend the walls, group together in places like a body of cells in an organism, then trail off in sparse directions with no indication of where the beginning or end is.

And of course, the most notably oppositional trait of his images that differentiates his work from nearly anyone I can think of working today is the smallness of his images. There is sometimes a notion that if the work is big enough, one can enter it like a space or some kind of immersive, hyperreal experience. Yamamoto’s images are all 4x6” or smaller, often non-matching odd-sizes, and in a kind of beautiful détente to those prevailing photographic conventions, he creates a very effective and moving sense of entering a space wherein one has a complete immersive experience of the results of his photographic expression.

Of the diminutive size of his images, Yamamoto has said:

As you can see, my photos are small and seem old. In fact, I work so that they’re like that. I could wait 30 years before using them, but that’s impossible. So, I must age them. I take them out with me on walks, I rub them with my hands, this is what gives me my desired expression. This is called the process of forgetting or the production of memory. Because in old photos the memories are completely manipulated and it’s this that interests me and this is the reason that I do this work.

If I take small photos, it’s because I want to make them into the matter of memories. And it’s for this reason that I think the best format is one that is held in the hollow of the hand. If we can hold the photo in our hand, we can hold a memory in our hand. A little like when we keep a family photo with us.

Because of the intentionally non-specificity of his images (there is no emphasis to be found in the subjects of his images that would convey a particular sense of place, time or social conventions), I believe that his images function as more a screen for projection upon the symbolic unconscious, a kind of visual tarot. Subjects of some of his images: a dented globe, a pair of peacocks in full display, a lone cloud hovering above a goal post, an animal descending a mountain ridge—photographed at a severely decanted angle. What is the viewer of these images meant to do with them if not make personally symbolic associations with them? Relate to these objects as beautiful talismans or quietly charged archetypes?

In any case, Nakazora was my first “real” purchase, the one that made me a collector and an addict. And true to a true photobook addict’s form, even at twenty-four years old and even funded with federally backed student loans, I purchased the limited edition that included a signed artist’s print.

Also magical thinking: at the time I thought it was a steal.

Proof of present magical thinking: it was.

If I love Yamamoto’s work in experiential viewing form, what then is there to be gained from owning one of his books? Well, I think the most unimaginative photobook possible is the one that is meant to replicate the gallery or museum experience. What you want in an artist’s book is an entirely other encounter, one that becomes more between just yourself and the artist. Yamamoto exceeds in this realm, creating a one-on-one conversation with you through inventive formats such as scrolls, wood-bound accordion books, oversized monographs with immense expanses of white space for his photographs to float in the same manner that they do on the wall or in the mind. Said another way: experiencing Yamamoto’s work on the wall is the giddy crush of a one-time romantic chance encounter, and the books are the ongoing affair that lasts for years.

Twenty years have passed since that first fated purchase, and in that time I have happily become more things besides: a photographer, a writer and editor, an educator, someone who regularly treats her body to maximum heart rate status through exercise, a mother and someone even more hopelessly caught up in the world of images than ever before.

From Nazraeli Press (upon publication): "Dictionary Definition of Nakazora: The space between sky and earth, the place where birds, etc. fly. Empty air. An internal hollow. Vague. Hollow. Around the center of the sky. Or, emptiness. A state when the feet do not touch the ground. Inattentiveness. The inability to decide between two things. Midway. The center of the sky (the zenith). A Buddhist term.

In this twenty-odd years of image-making, image-thinking and image-mongering, I have also totally burnt out on every facet of this calling, multiple times. Each occasion that this has happened, in addition to some pretty stringent palate cleansing, I’ve had to find my way back to this thing that I love in a manner that approaches feeling right and true. This might be the third time? In any case, this site is my bid for my autonomy from and my imminent next marriage to photography’s inexhaustible, chimeric self. A blog. A blog? How quaint. And it’s just about photobooks. I’ll leave it to the other full-time writers and cultural critics to focus on the 360° view of the medium—it is too much and much too stressful for me to keep on top of or straight in my mind. This space is just for the contemplation, discussion and, probably, enabling of a photobook addict—that is to say, me—and those of you hiding in the shadows of your bookcases and own magical thinking.

Welcome.

Feel free to say hi, share your gateway drug, current additions, or even what you just bought because #worldphotobookday. Comments enabled on this site.